Book:

The Opéra Book, 10 pages,

14 Nov. 2022, DE

EDITED BY MATTHIAS STRAUB

DESIGNED BY STEFFEN KNÖLL

DESIGNED BY SVEN TILLACK

Limited anniversary issue of The Opéra – Magazine for Contemporary Nude Photography – including its most famous positions of the past as well as new views on the human body

Full Description: Since the founding of The Opéra – Magazine for Contemporary Nude Photography in 2012, a new issue with works by more than 30 photographers per magazine has been produced each year under the creative direction of changing designers. The most beautiful series from 10 issues are now being published for the first time and in a new layout within part new motifs in a unique omnibus volume. The dedication of each artist is also honoured in a personal text contribution.

Artists: Evelyn Bencicova, Rachel de Joode, Henny de la Motte, Fabien Dettori, Julia Fullerton-Batten, Thomas Hauser, Bart Hess, Petrina Hicks, Mayumi Hosokura, David PD Hyde, Maciek Jasik, Nadav Kander, Mona Kuhn, Joanne Leah, Kenny Lemes, Julia Luzina, Ed Maximus, Stefan Milev, Thomas Sing, Laura Stevens, Erika Svensson, Marc van Dalen, Sean Patrick Watters, Roger Weiss, Milena Wojhan, Bastiaan Woudt, Daisuke Yokota, Lin Zhipeng.

Publisher Kerber

ISBN 9783735608529

Publish date 14th Nov 2022

Binding Hardback

Territory World excluding Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the US & Canada

Size 310 mm x 240 mm

Price €180

Pages 320 Pages

Illustrations 205 color, 69 b&w

Roger Weiss

The Opéra Book, 10 pages,

14 Nov. 2022, DE

EDITED BY MATTHIAS STRAUB

DESIGNED BY STEFFEN KNÖLL

DESIGNED BY SVEN TILLACK

Limited anniversary issue of The Opéra – Magazine for Contemporary Nude Photography – including its most famous positions of the past as well as new views on the human body

Full Description: Since the founding of The Opéra – Magazine for Contemporary Nude Photography in 2012, a new issue with works by more than 30 photographers per magazine has been produced each year under the creative direction of changing designers. The most beautiful series from 10 issues are now being published for the first time and in a new layout within part new motifs in a unique omnibus volume. The dedication of each artist is also honoured in a personal text contribution.

Artists: Evelyn Bencicova, Rachel de Joode, Henny de la Motte, Fabien Dettori, Julia Fullerton-Batten, Thomas Hauser, Bart Hess, Petrina Hicks, Mayumi Hosokura, David PD Hyde, Maciek Jasik, Nadav Kander, Mona Kuhn, Joanne Leah, Kenny Lemes, Julia Luzina, Ed Maximus, Stefan Milev, Thomas Sing, Laura Stevens, Erika Svensson, Marc van Dalen, Sean Patrick Watters, Roger Weiss, Milena Wojhan, Bastiaan Woudt, Daisuke Yokota, Lin Zhipeng.

Publisher Kerber

ISBN 9783735608529

Publish date 14th Nov 2022

Binding Hardback

Territory World excluding Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the US & Canada

Size 310 mm x 240 mm

Price €180

Pages 320 Pages

Illustrations 205 color, 69 b&w

Book:

Doppelgänger: Image of the Human Being by Gestalten, DE

2 pages

The digital age has fundamentally changed traditional notions of who we are and how we wish to be perceived. The music producer Chris Walla puts it this way: “Confronted with our significantly more banal everyday life, we’re measuring our actual selves against our online selves with hopeful resignation.”

Doppelganger presents current trends in the depiction of human beings. In today s images and sculptures, personal identities are being intensified, altered, or created through the use of techniques such as deformation and construction/deconstruction as well as the obliteration of classical proportions, visual traditions, and what is generally considered beautiful and fashionable. The book shows permutations of the outer human shell created with costumes and masks as well as photo-technical and artistic manipulation. These take their visual cues from such diverse aesthetics as Dada, surrealism, high tech, cutting-edge fashion design, and the folklore of other cultures. Masquerades and artificial characters are used imaginatively to enhance and obscure true identities. With examples ranging from the intimate to the radical, Doppelganger explores how many or how few effects the depiction of a person can take in order to function as such. In doing so, the book shows that the unique visual appearances being created today often reveal more about the identities of their subjects and creators than their real faces ever could.

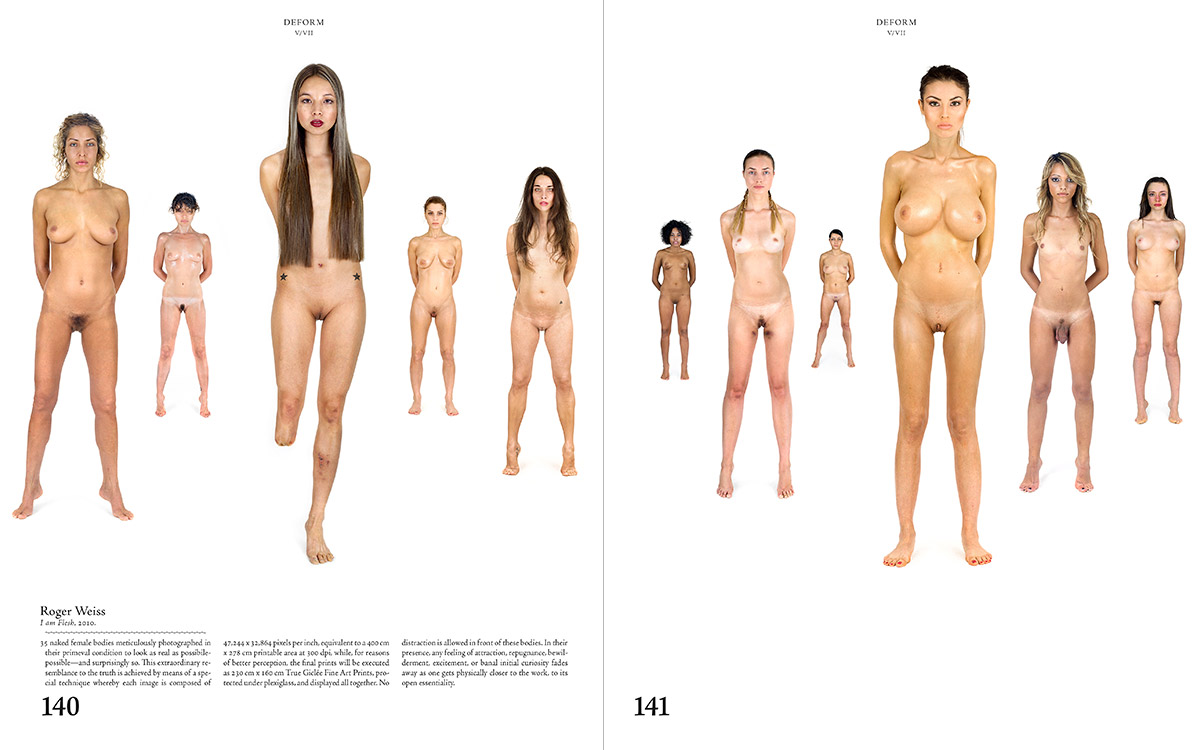

“In “I am Flesh” bodies represent reality: 35 naked female bodies meticulously photographed in their primeval condition to look as real as possible - and surprisingly so. This extraordinary resemblance to reality is achieved through a special technique that has every image made of 47,244 x 32,864 pixels per inch, equivalent to 400 X 278 cm printable area at 300 dpi, while, for reasons of better perception, the final prints will be executed as 230 cm x 160 cm True Giclée Fine Art Prints, protected under plexiglass, and displayed all together. No distraction is allowed in front of these bodies. In their presence, any feeling of attraction, repugnance, bewilderment, excitement, or banal initial curiosity fades away as one gets physically closer to the work, to its open essentiality”.

Title Doppelganger

Subtitle Images of the Human Being

Publisher Gestalten

Editors R. Klanten, S. Ehmann, F. Schulze

Format 24 x 30 cm

Dimensions 9.45 x 0.94 x 12.01 inches

Features 235 pages, full color, hardcover

ISBN-10 3899553322

ISBN-13 978-3-89955-332-1

Price €39.90 | $60.00 | £37.50

European Release: January 2011

International Release: February 2011

Language English

Item Weight 3.67pounds

I am Flesh

Doppelgänger: Image of the Human Being by Gestalten, DE

2 pages

The digital age has fundamentally changed traditional notions of who we are and how we wish to be perceived. The music producer Chris Walla puts it this way: “Confronted with our significantly more banal everyday life, we’re measuring our actual selves against our online selves with hopeful resignation.”

Doppelganger presents current trends in the depiction of human beings. In today s images and sculptures, personal identities are being intensified, altered, or created through the use of techniques such as deformation and construction/deconstruction as well as the obliteration of classical proportions, visual traditions, and what is generally considered beautiful and fashionable. The book shows permutations of the outer human shell created with costumes and masks as well as photo-technical and artistic manipulation. These take their visual cues from such diverse aesthetics as Dada, surrealism, high tech, cutting-edge fashion design, and the folklore of other cultures. Masquerades and artificial characters are used imaginatively to enhance and obscure true identities. With examples ranging from the intimate to the radical, Doppelganger explores how many or how few effects the depiction of a person can take in order to function as such. In doing so, the book shows that the unique visual appearances being created today often reveal more about the identities of their subjects and creators than their real faces ever could.

“In “I am Flesh” bodies represent reality: 35 naked female bodies meticulously photographed in their primeval condition to look as real as possible - and surprisingly so. This extraordinary resemblance to reality is achieved through a special technique that has every image made of 47,244 x 32,864 pixels per inch, equivalent to 400 X 278 cm printable area at 300 dpi, while, for reasons of better perception, the final prints will be executed as 230 cm x 160 cm True Giclée Fine Art Prints, protected under plexiglass, and displayed all together. No distraction is allowed in front of these bodies. In their presence, any feeling of attraction, repugnance, bewilderment, excitement, or banal initial curiosity fades away as one gets physically closer to the work, to its open essentiality”.

Title Doppelganger

Subtitle Images of the Human Being

Publisher Gestalten

Editors R. Klanten, S. Ehmann, F. Schulze

Format 24 x 30 cm

Dimensions 9.45 x 0.94 x 12.01 inches

Features 235 pages, full color, hardcover

ISBN-10 3899553322

ISBN-13 978-3-89955-332-1

Price €39.90 | $60.00 | £37.50

European Release: January 2011

International Release: February 2011

Language English

Item Weight 3.67pounds

Book:

Seltmann Publishers, DE

11 pages

18 Jan. 2024, DE

Bereits zum 10. Mal wird mit der Ausstellungsreihe FUMES AND PERFUMES eine einzigartige und außergewöhnliche Ausstellungsfläche in der Stuttgarter Innenstadt bespielt: Das Züblin Parkhaus. Neben ihren jüngsten Arbeiten, präsentiert die Stuttgarter Fotografen- und Kuratorengruppe Werke von renommierten internationalen Fotokünstlern.

Die großformatigen Fotodrucke kontrastieren mit dem sonst kahlen Zweckbau, laden zum Erleben, Entdecken und Verweilen ein. Ein ganzjährig frei zugängliches Kunsterlebnis, an einem überraschenden Ausstellungsort!

Auch dieses Mal werden wieder einzelne Fotodrucke im Parkhaus von Stuttgarter Künstlern bemalt und in neue Werke umgestalltet. Es entsteht spannende „Crossover“ Kunst im Spannungsfeld zwischen Fotografie und Malerei. DAVIDE JUST, FRIEDERIKE JUST, ROMAN MARES, RAHEL ROSENBERGER und DANIELLE ZIMMERMANN.

Neben sagenhafter Fotokunst, coolen Drinks und zwanglosem get together, lockt der Eröffnungsabend auch mit tollen Projektionen von LAURENZ THEINERTs VISUAL PIANO, musikalisch begleitet von MARTIN SCHNABEL und BO & HERB, einer Kunstperformance von JENNY WINTER-STOJANOVIC, sowie einer electronic live performance von MATTEO JUST feat. CLEMENS BUCHTA.

Die Ausstellung bleibt bis Ende 2023 bestehen und kann täglich zwischen 6:00 und 22:00 Uhr auch ohne Parkschein besucht werden.

290 Seiten, Hardcover

Deutsch mit englischen Übersetzungen / german with english translations

Seltmann Publishers 2024

ISBN 978-3-949070-49-5

Fumes and Perfumes

Herausgeber / Editors: Frank Bayh & Steff Rosenberger-Ochs, Peter Franck, Bernd Kammerer, Monica Menez und Yves Noir.Seltmann Publishers, DE

11 pages

18 Jan. 2024, DE

Bereits zum 10. Mal wird mit der Ausstellungsreihe FUMES AND PERFUMES eine einzigartige und außergewöhnliche Ausstellungsfläche in der Stuttgarter Innenstadt bespielt: Das Züblin Parkhaus. Neben ihren jüngsten Arbeiten, präsentiert die Stuttgarter Fotografen- und Kuratorengruppe Werke von renommierten internationalen Fotokünstlern.

Die großformatigen Fotodrucke kontrastieren mit dem sonst kahlen Zweckbau, laden zum Erleben, Entdecken und Verweilen ein. Ein ganzjährig frei zugängliches Kunsterlebnis, an einem überraschenden Ausstellungsort!

Auch dieses Mal werden wieder einzelne Fotodrucke im Parkhaus von Stuttgarter Künstlern bemalt und in neue Werke umgestalltet. Es entsteht spannende „Crossover“ Kunst im Spannungsfeld zwischen Fotografie und Malerei. DAVIDE JUST, FRIEDERIKE JUST, ROMAN MARES, RAHEL ROSENBERGER und DANIELLE ZIMMERMANN.

Neben sagenhafter Fotokunst, coolen Drinks und zwanglosem get together, lockt der Eröffnungsabend auch mit tollen Projektionen von LAURENZ THEINERTs VISUAL PIANO, musikalisch begleitet von MARTIN SCHNABEL und BO & HERB, einer Kunstperformance von JENNY WINTER-STOJANOVIC, sowie einer electronic live performance von MATTEO JUST feat. CLEMENS BUCHTA.

Die Ausstellung bleibt bis Ende 2023 bestehen und kann täglich zwischen 6:00 und 22:00 Uhr auch ohne Parkschein besucht werden.

290 Seiten, Hardcover

Deutsch mit englischen Übersetzungen / german with english translations

Seltmann Publishers 2024

ISBN 978-3-949070-49-5

Magazine:

Carnale, IT

8 pages + limited edition poster of 100 (mm2030x1400)

CARNALE MAGAZINE

Issue 03 - Sept. 2022

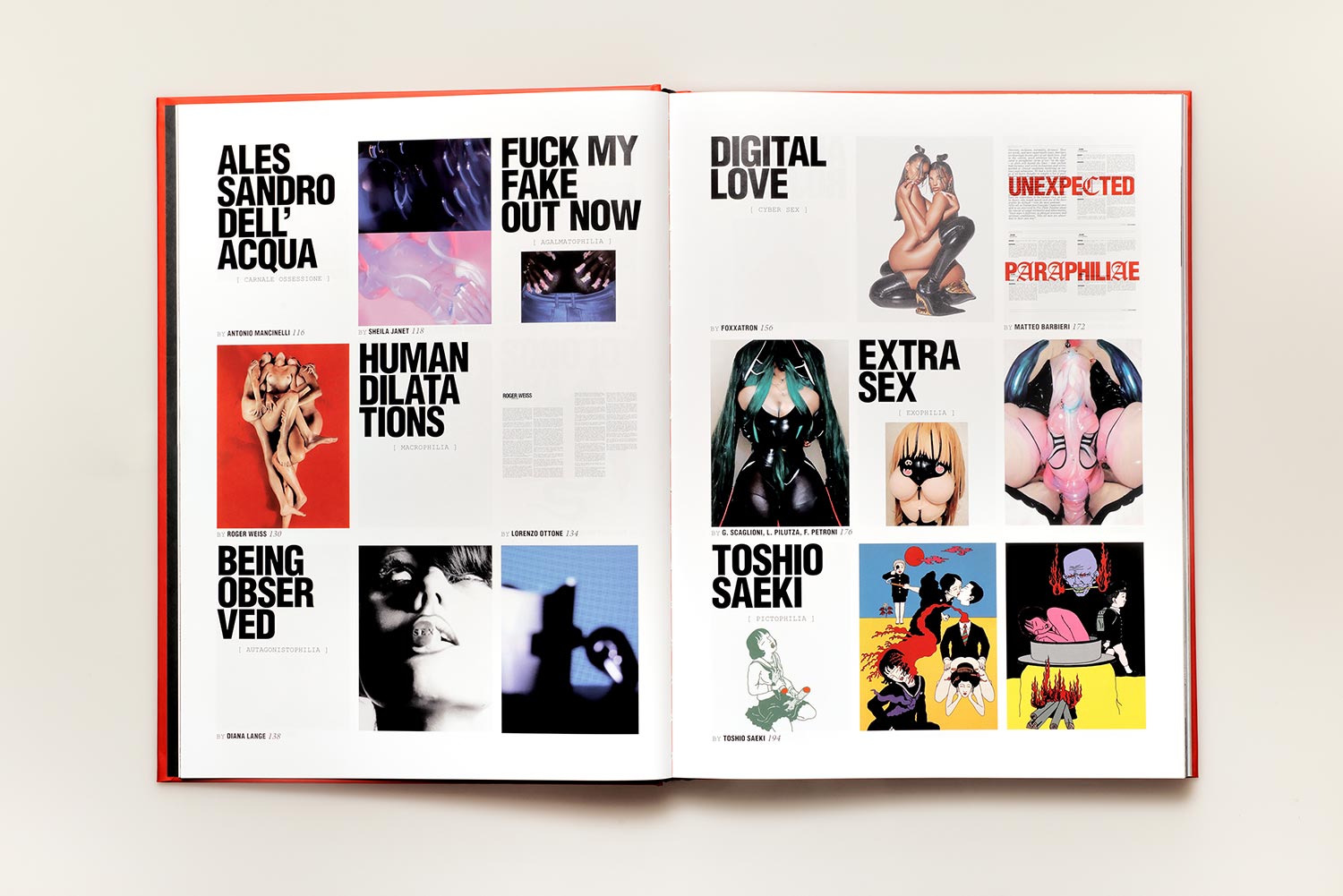

CARNALE OSSESSIONE

Interview by Lorenzo Ottone

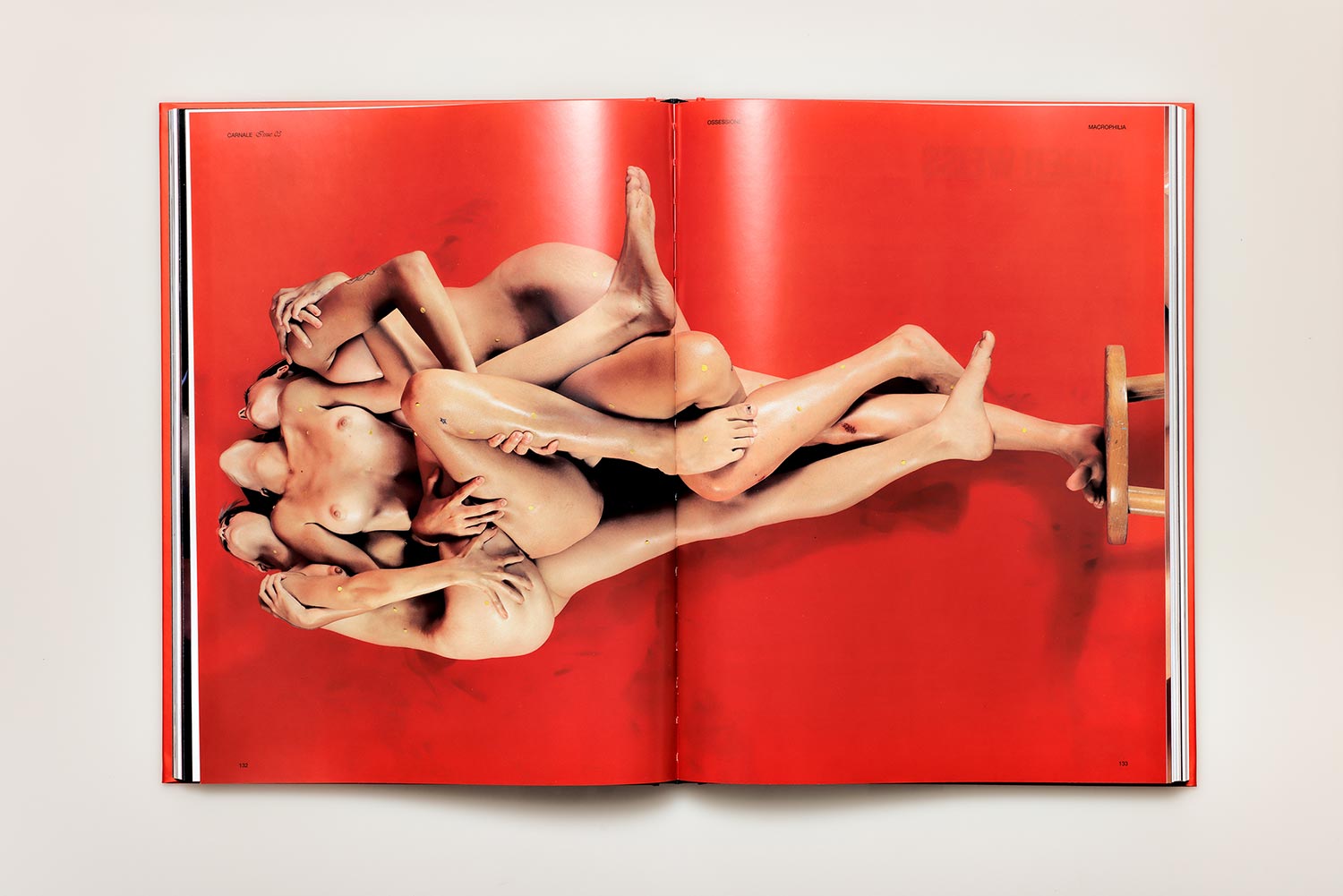

There’s an episode directed by Carlo Lizzani, in the anthology film Thrilling (1965), where the

protagonist – played by Alberto Sordi – exits the Autostrada del Sole to take a country road. There, he finds one of those pensions/guesthouses that had given drivers a place to recoup before Italy’s economic boom, but had seen their revenues, and their future, vanish once the motorway opened. It turns out to be a murder mystery with a tinge of Mediterranean and Boccaccio, but also an example of detours and new life perspectives that open us up to unexpected glimpses, such as those that follow.

I was reminded of this episode as I talked with photographer Roger Weiss, listening to him making an ardent case for the importance of knowing how to change perspectives in life. An almost spiritual, rather than artistic manifesto, inspiring his work.

“Once there is a motorway, people don’t drive along other little roads,” says Weiss. He mentions this as he reflects on the dangers of homologation that social media can lead to, not only for artists. However, we might have to start from social media – where the broken-up and recomposed bodies immortalized by Weiss have managed to stand out – to retrace his journey and better understand the deepest meaning of his work, looking past the two-dimensional and hectic nature of the medium.

Today, Weiss says, in a context of “globalization and widespread risk of cultural leveling, when people start in one direction they need to be able to define their own perimeters, which they then break down in order to build new ones.” Instead, creativity can encounter major obstacles when having to act without self-awareness or self-criticism, within criteria that often have been defined “using algorithms that do not represent what they were built for.” The same can be said of hinging one’s art on bodies, bared yet certainly not bare, in times when “we have a heightened awareness of the power of aesthetics,” even at a very young age. “It’s hard to generalize, but we struggle to develop different visions,” the photographer comments.

Weiss speaks with the prophetic awareness of the artist as homo virtus, a figure with a thirst for knowledge and moral lucidity that seems out of place in this day and age – when art appears enslaved to digital communication, and new “artists” are proclaimed with the same frenetic ease of a simple like. After all, the philosophy at the heart of Roger’s work has a strong spiritual component, more shamanic in nature than tied to a particular religion. It emerges in the vision of his subjects as primordial and totemic figures, “antennas pointing to the sky, elements that can lead us back to a dimension of life that is less artificial or tied to the toys we surround ourselves with.” His research appears clear in the decision to cancel the limits of depth of field in favor of the vertical element, turning him into an architect of bodies.

Hence Weiss’s awareness that he cannot consider himself as just a photographer, but rather as a person destined to move through the beauties of the planet for a limited period of time. “By deconstructing and reconstructing figures, I carry out a continuous, perhaps illusory, search for the moment in which we are at one with everything, as if it were a ritual, or a mantra that is fulfilled within the four or five days in which I work full-time at a piece.”

Thus, his subject-monoliths represent the moment in which the artist manages to feel part of a whole, on an axis between the earthly and the otherworldly dimensions, a bridge between the past and the future of human civilization. “Descartes spoke of the pineal gland, as the intersection between the spiritual dimension and everyday life. I like to think of my works as something similar,” Roger admits.

Indeed, Weiss’s modus operandi is far from the method traditionally associated with photographers. His post-production process turns out to be, upon closer inspection, a truly creative phase. A complex journey in which the artist becomes the demiurge of a new image with what we may call a (neo) Cubist attitude. Although the final result does not convey the aesthetic features of that movement, it brings it back to life through a process that entails breaking apart sequences of photographs into hundreds of frames, which are then put back together to create subjects in a renewed perspective. A process that, despite the works being often viewed in digital form, requires cutting and reassembling the photos in Moleskine notebooks, as the photographer’s analogic studying grounds.

“I break apart people while they are posing, disassemble them piece by piece; I internalize them, make them my own, and in a week I reassemble them. There is a lot of me in the final result, and very little of the person I portrayed.”

Weiss, once again, gives a spiritual interpretation of this final synthesis. “Just like you cannot see what is before or after life, in my work these phases are canceled by the final outcome.”

This psychological process explains the photographer’s attraction towards the female body. On the one hand there is the mystery of the opposite sex and the curiosity to explore it, while on the other there are women and their wombs as a symbolic, ancestral passageway between what is before and what is after life.

The choice of turning faces upwards expresses the will to avoid confronting subjects through their faces, allowing for greater creative freedom. Viewers do not benefit from a face-to-face encounter with the subject, but their gaze is inevitably led upwards – also through the choice of printing on a scale larger than the actual size of the models portrayed. Weiss, however, is keen to clarify that his work is not meant to deform bodies, but to play with natural perspectives through the use of multiple lenses. A dynamic he likens more to the architectural momentum of Gothic cathedrals than to photography, which Weiss confesses he does not love particularly.

“Compared to other forms of art, there are few [photographers] who impress me – such as some exponents of the Düsseldorf School. When I was very young, photography was functional because it allowed me to keep a certain distance, while still exploring a subject and witnessing a moment. It was like a therapy session.” One might wonder to what extent the naked bodies Weiss portrays are flesh, and to what extent they are fleshly. The human body is not explored in a voyeuristic way as much as studied from a distance, filtered using the lens, with an approach that stems from the psyche of the artist when he was a boy.

“When I was little, I struggled with not being able to understand what made the human body beautiful. I saw noses, hands, ears, and all the other parts of the body in terms of their practical function, but I could not grasp their aesthetic value,” the photographer shares.

Hence his fascination with anatomical details, sectioned and mapped, and his approach to the human body where “every erotic element falls away”.

The subject’s nudity is thus functional to minimize the human tension that forms between model and photographer. Weiss explains he feels vested with the responsibility deriving from a body being entrusted to his lens – a burden he felt even more before starting his professional career, when friends or amateur models were the ones undressing in front of his camera. The act also revealed physical – and sometimes psychological – scars. This is why, to this day, Weiss claims that photography as a form of personal research, outside of the world of fashion and professional models, allows for the most interesting friction between photographer and subject to emerge.

This research led him to shy away from alternative models, which are so on trend today. “I’ve been asked why I so often use good-looking girls. If I photographed disfigured or elderly bodies, it would undoubtedly be easier to attract attention [to my work], I would have more disturbing elements to use. I am interested in totems devoid of obvious signs: otherwise I’d see nothing but these signs in my mapping.” His words sound curious on the phone, as he speaks from a beach on the last day of holiday before returning home, in a town in Switzerland. Weiss’s geographical situation reflects his human condition: a caustic and shy detachment that seems to transpire from the memories of his debut in photography, and of the role – almost more functional than artistic – this discipline has taken on for him.

He often ends up emphasizing the importance of balance, in life as well as in art, in the search for in medium veritas.

Photography as a form of independent research must be able to fit in with the photography that lends itself to fashion and editorial work. “I tend to hide my work in fashion, because I’m mostly interested in showing my artistic side,” Roger explains, with the wisdom of someone who’s aware it would be childish, and useless, to refuse at all costs the state of the industry and the norms of contemporaneity. “I believe exploring Instagram is essential today. Brands select artists and creatives through social media, which are incredible, extremely powerful channels. I find that experimenting commercially can increase your work’s fame exponentially. However, it’s still important to find balance, as indeed in all directions of life. It takes dosis.” Thus, being able to integrate pragmatic styling with the totemic and timeless sacredness of a naked body is also a matter of balance.

A challenge that is intensified by the times we live in, when – according to Weiss – “the idea of experiencing the aesthetic dimension cerebrally, rather than physically, is much stronger than in the past.” With all the contradictions of digital platforms, of course: the first to offer tools that instantly alter our faces and, at the same time, the media that continue to censor bodies in their most natural and ancestral form, when they are naked.

Considering the frenzy of digital life, we might naturally wonder whether Weiss’s works, shared on social media, are not likely to generate the opposite of the effect he intended and to perpetuate the pursuit of idealized aesthetic canons.

“I hope curious viewers will carry out their own process of body decoding. Rodin was a model for me in this sense, because in his work we find a fracture between how the skeletal structure works and what the audience sees. The muscles at rest are contracted, and vice versa the flexed parts are left soft. As a consequence, a careful look allows viewers to distance themselves from their previous cultural experience, and to reinterpret the works without using what they already knew.”

Before hanging up, Roger insists on sharing something he deeply cares about. His wish to leave a mark through his works, like ancient civilizations did with totems, temples and cathedrals.

“Now, as years go by, I would like to gradually move away from chaos. I would like to consider myself a bit like The Man Who Planted Trees that Jean Giono wrote about.”

Who knows what future generations will see in Roger Weiss’s carnal totems. Our wish is that they survive, like monoliths, to the frenzy of our times, and remain as the fruit of questions, studies and inspiration to decipher the mystery of our bodies and, therefore, of our existence.

Human Dilatations

Carnale, IT

8 pages + limited edition poster of 100 (mm2030x1400)

CARNALE MAGAZINE

Issue 03 - Sept. 2022

CARNALE OSSESSIONE

Interview by Lorenzo Ottone

There’s an episode directed by Carlo Lizzani, in the anthology film Thrilling (1965), where the

protagonist – played by Alberto Sordi – exits the Autostrada del Sole to take a country road. There, he finds one of those pensions/guesthouses that had given drivers a place to recoup before Italy’s economic boom, but had seen their revenues, and their future, vanish once the motorway opened. It turns out to be a murder mystery with a tinge of Mediterranean and Boccaccio, but also an example of detours and new life perspectives that open us up to unexpected glimpses, such as those that follow.

I was reminded of this episode as I talked with photographer Roger Weiss, listening to him making an ardent case for the importance of knowing how to change perspectives in life. An almost spiritual, rather than artistic manifesto, inspiring his work.

“Once there is a motorway, people don’t drive along other little roads,” says Weiss. He mentions this as he reflects on the dangers of homologation that social media can lead to, not only for artists. However, we might have to start from social media – where the broken-up and recomposed bodies immortalized by Weiss have managed to stand out – to retrace his journey and better understand the deepest meaning of his work, looking past the two-dimensional and hectic nature of the medium.

Today, Weiss says, in a context of “globalization and widespread risk of cultural leveling, when people start in one direction they need to be able to define their own perimeters, which they then break down in order to build new ones.” Instead, creativity can encounter major obstacles when having to act without self-awareness or self-criticism, within criteria that often have been defined “using algorithms that do not represent what they were built for.” The same can be said of hinging one’s art on bodies, bared yet certainly not bare, in times when “we have a heightened awareness of the power of aesthetics,” even at a very young age. “It’s hard to generalize, but we struggle to develop different visions,” the photographer comments.

Weiss speaks with the prophetic awareness of the artist as homo virtus, a figure with a thirst for knowledge and moral lucidity that seems out of place in this day and age – when art appears enslaved to digital communication, and new “artists” are proclaimed with the same frenetic ease of a simple like. After all, the philosophy at the heart of Roger’s work has a strong spiritual component, more shamanic in nature than tied to a particular religion. It emerges in the vision of his subjects as primordial and totemic figures, “antennas pointing to the sky, elements that can lead us back to a dimension of life that is less artificial or tied to the toys we surround ourselves with.” His research appears clear in the decision to cancel the limits of depth of field in favor of the vertical element, turning him into an architect of bodies.

Hence Weiss’s awareness that he cannot consider himself as just a photographer, but rather as a person destined to move through the beauties of the planet for a limited period of time. “By deconstructing and reconstructing figures, I carry out a continuous, perhaps illusory, search for the moment in which we are at one with everything, as if it were a ritual, or a mantra that is fulfilled within the four or five days in which I work full-time at a piece.”

Thus, his subject-monoliths represent the moment in which the artist manages to feel part of a whole, on an axis between the earthly and the otherworldly dimensions, a bridge between the past and the future of human civilization. “Descartes spoke of the pineal gland, as the intersection between the spiritual dimension and everyday life. I like to think of my works as something similar,” Roger admits.

Indeed, Weiss’s modus operandi is far from the method traditionally associated with photographers. His post-production process turns out to be, upon closer inspection, a truly creative phase. A complex journey in which the artist becomes the demiurge of a new image with what we may call a (neo) Cubist attitude. Although the final result does not convey the aesthetic features of that movement, it brings it back to life through a process that entails breaking apart sequences of photographs into hundreds of frames, which are then put back together to create subjects in a renewed perspective. A process that, despite the works being often viewed in digital form, requires cutting and reassembling the photos in Moleskine notebooks, as the photographer’s analogic studying grounds.

“I break apart people while they are posing, disassemble them piece by piece; I internalize them, make them my own, and in a week I reassemble them. There is a lot of me in the final result, and very little of the person I portrayed.”

Weiss, once again, gives a spiritual interpretation of this final synthesis. “Just like you cannot see what is before or after life, in my work these phases are canceled by the final outcome.”

This psychological process explains the photographer’s attraction towards the female body. On the one hand there is the mystery of the opposite sex and the curiosity to explore it, while on the other there are women and their wombs as a symbolic, ancestral passageway between what is before and what is after life.

The choice of turning faces upwards expresses the will to avoid confronting subjects through their faces, allowing for greater creative freedom. Viewers do not benefit from a face-to-face encounter with the subject, but their gaze is inevitably led upwards – also through the choice of printing on a scale larger than the actual size of the models portrayed. Weiss, however, is keen to clarify that his work is not meant to deform bodies, but to play with natural perspectives through the use of multiple lenses. A dynamic he likens more to the architectural momentum of Gothic cathedrals than to photography, which Weiss confesses he does not love particularly.

“Compared to other forms of art, there are few [photographers] who impress me – such as some exponents of the Düsseldorf School. When I was very young, photography was functional because it allowed me to keep a certain distance, while still exploring a subject and witnessing a moment. It was like a therapy session.” One might wonder to what extent the naked bodies Weiss portrays are flesh, and to what extent they are fleshly. The human body is not explored in a voyeuristic way as much as studied from a distance, filtered using the lens, with an approach that stems from the psyche of the artist when he was a boy.

“When I was little, I struggled with not being able to understand what made the human body beautiful. I saw noses, hands, ears, and all the other parts of the body in terms of their practical function, but I could not grasp their aesthetic value,” the photographer shares.

Hence his fascination with anatomical details, sectioned and mapped, and his approach to the human body where “every erotic element falls away”.

The subject’s nudity is thus functional to minimize the human tension that forms between model and photographer. Weiss explains he feels vested with the responsibility deriving from a body being entrusted to his lens – a burden he felt even more before starting his professional career, when friends or amateur models were the ones undressing in front of his camera. The act also revealed physical – and sometimes psychological – scars. This is why, to this day, Weiss claims that photography as a form of personal research, outside of the world of fashion and professional models, allows for the most interesting friction between photographer and subject to emerge.

This research led him to shy away from alternative models, which are so on trend today. “I’ve been asked why I so often use good-looking girls. If I photographed disfigured or elderly bodies, it would undoubtedly be easier to attract attention [to my work], I would have more disturbing elements to use. I am interested in totems devoid of obvious signs: otherwise I’d see nothing but these signs in my mapping.” His words sound curious on the phone, as he speaks from a beach on the last day of holiday before returning home, in a town in Switzerland. Weiss’s geographical situation reflects his human condition: a caustic and shy detachment that seems to transpire from the memories of his debut in photography, and of the role – almost more functional than artistic – this discipline has taken on for him.

He often ends up emphasizing the importance of balance, in life as well as in art, in the search for in medium veritas.

Photography as a form of independent research must be able to fit in with the photography that lends itself to fashion and editorial work. “I tend to hide my work in fashion, because I’m mostly interested in showing my artistic side,” Roger explains, with the wisdom of someone who’s aware it would be childish, and useless, to refuse at all costs the state of the industry and the norms of contemporaneity. “I believe exploring Instagram is essential today. Brands select artists and creatives through social media, which are incredible, extremely powerful channels. I find that experimenting commercially can increase your work’s fame exponentially. However, it’s still important to find balance, as indeed in all directions of life. It takes dosis.” Thus, being able to integrate pragmatic styling with the totemic and timeless sacredness of a naked body is also a matter of balance.

A challenge that is intensified by the times we live in, when – according to Weiss – “the idea of experiencing the aesthetic dimension cerebrally, rather than physically, is much stronger than in the past.” With all the contradictions of digital platforms, of course: the first to offer tools that instantly alter our faces and, at the same time, the media that continue to censor bodies in their most natural and ancestral form, when they are naked.

Considering the frenzy of digital life, we might naturally wonder whether Weiss’s works, shared on social media, are not likely to generate the opposite of the effect he intended and to perpetuate the pursuit of idealized aesthetic canons.

“I hope curious viewers will carry out their own process of body decoding. Rodin was a model for me in this sense, because in his work we find a fracture between how the skeletal structure works and what the audience sees. The muscles at rest are contracted, and vice versa the flexed parts are left soft. As a consequence, a careful look allows viewers to distance themselves from their previous cultural experience, and to reinterpret the works without using what they already knew.”

Before hanging up, Roger insists on sharing something he deeply cares about. His wish to leave a mark through his works, like ancient civilizations did with totems, temples and cathedrals.

“Now, as years go by, I would like to gradually move away from chaos. I would like to consider myself a bit like The Man Who Planted Trees that Jean Giono wrote about.”

Who knows what future generations will see in Roger Weiss’s carnal totems. Our wish is that they survive, like monoliths, to the frenzy of our times, and remain as the fruit of questions, studies and inspiration to decipher the mystery of our bodies and, therefore, of our existence.